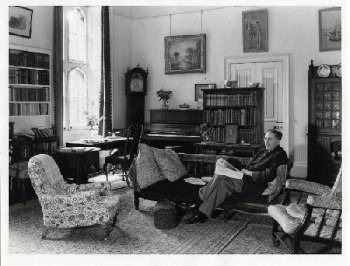

One of the highlights of my student career was meeting E.M. Forster. Carol (my first wife) and I were members of the Cambridge Humanists, and the society threw a party for Forster on his 90th birthday. It was held in King’s, where he was a Life Fellow (the photograph, taken in 1968, shows him in his Set) and hosted by Francis Crick who — as a Nobel laureate — was Cambridge’s most prominent humanist at the time (and may even have been the society’s Patron). Forster was in a chair (it may have been wheelchair — on that my memory is foggy) and sat quietly while a good deal of celebratory bedlam — which he viewed with a mildly quizzical expression — went on around him.

As someone whose pet hate is people who are endowed with certainty: religious fundamentalists, for example and ideological fanatics — I’ve always admired Forster for his uncertainty, open-mindedness and willingness to entertain the thought that he might be wrong. So the works of his that I’ve enjoyed most have been his essays, and the broadcast talks he gave on the BBC. Which is why it’s wonderful to discover that the collected talks have now been published in a handsome, footnoted edition.

Zadie Smith (whose novel On Beauty was allegedly inspired by Forster’s Howard’s End) has written a thoughtful review in the current issue of the New York Review of Books. “In the taxonomy of English writing”, she writes,

E.M. Forster is not an exotic creature. We file him under Notable English Novelist, common or garden variety. Still, there is a sense in which Forster was something of a rare bird. He was free of many vices commonly found in novelists of his generation—what’s unusual about Forster is what he didn’t do. He didn’t lean rightward with the years, or allow nostalgia to morph into misanthropy; he never knelt for the Pope or the Queen, nor did he flirt (ideologically speaking) with Hitler, Stalin, or Mao; he never believed the novel was dead or the hills alive, continued to read contemporary fiction after the age of fifty, harbored no special hatred for the generation below or above him, did not come to feel that England had gone to hell in a hand-basket, that its language was doomed, that lunatics were running the asylum, or foreigners swamping the cities.

Smith’s angle is that Forster was the ultimate middleman. He was, she thinks,

a tricky bugger. He made a faith of personal sincerity and a career of disingenuousness. He was an Edwardian among Modernists, and yet—in matters of pacifism, class, education, and race—a progressive among conservatives. Suburban and parochial, his vistas stretched far into the East. A passionate defender of “Love, the beloved republic,” he nevertheless persisted in keeping his own loves secret, long after the laws that had prohibited honesty were gone. Between the bold and the tame, the brave and the cowardly, the engaged and the complacent, Forster walked the middling line.

I’ve always thought of him as the epitomé of mild common sense. He understood the primacy of friendship, for example, and his aphorism about it (that if he had to choose between betraying his country and betraying his friend he hoped he’d have the courage to do the former) is a pretty good guide for living. And, when one remembers the jingoistic times in which he said that, it’s a aphorism that took courage to articulate.

In fact, he’s always seemed to me to be, in his mild-mannered way, rather courageous. He was a distinguished humanist, but one who recognised that the creed had its weaknesses: “the humanist shirks responsibility”, he wrote, “dislikes making decisions, and is sometimes a coward”. But during the war and the years running up to it Forster didn’t display much cowardice. He ridiculed Nazi “philosophy” from the early 1930s onward, attacked the prison and police systems, defended the Third Program, spoke up for mass education, the rights of refugees, free concerts for the poor, and art for the masses. In other words, he kept faith with liberal principles that many of his more cocksure contemporaries abandoned. “Do we, in these terrible times”, he asked, “want to be humanists or fanatics? I have no doubt as to my own wish, I would rather be a humanist with all his faults, than a fanatic with all his virtues.”

Right on.