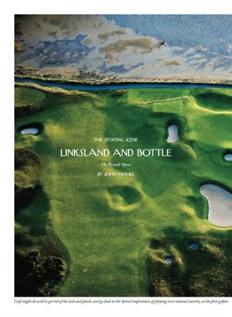

The September 6 edition of the New Yorker has a lovely piece (sadly, behind a paywall) by John McPhee about this year’s British Open, which was played on the Old Course at St Andrews. At one point, McPhee walked the course with David Hamilton, a noted golf historian, who drew attention to

certain “Presbyterian features” of the course — the Valley of Sin, the Pulpit bunker, the bunker named Hell — pointing them out as we passed them. St Andrews’ pot bunkers are nothing like the scalloped sands of other courses. The many dozens of them on the Old Course are small, cylindrical, scarcely wider than a golf swing, and of varying depth — four feet, six feet, but always enough to retain a few strokes. Their faces are vertical, layered, stratigraphic walls of ancestral turf. As you look down a fairway, they suggest the mouths of small caves, or, collectively, the sharp perforations of a kitchen grater. On the sixteenth, he called attention to a pair of them in mid-fairway, only a yard or two apart, with a mound between them that suggested cartilage. The name of this hazard is the Principal’s Nose. Hamilton told a joke about a local man playing the course, who suffered a seizure at the Principal’s Nose. His playing partner called 999, the UK version of 911, and was soon speaking with a person in Bangalore. The playing partner reported the seizure and said that the victim was at the Principal’s Nose bunker on the sixteenth hole on the Old Course at St Andrews, in Scotland; and Bangalore asked, “Which nostril?”

It’s a lovely piece, in all kinds of ways. And very good on the touchy subject of the seventeenth hole, which is almost as fiendish as the fifth in Lahinch.