Gateway to ‘Global Britain’

Heathrow Airport Terminal 2, on a quiet Saturday afternoon.

Quote of the Day

”He who hesitates is poor.”

- Mel Brooks

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Mark Knopfler | Two Pairs Of Hands

Long Read of the Day

Why trade unions matter

Interesting and perceptive Long Read by Neil Bierbaum.

During performance related workshops, the question comes up about expectations; what to do about bosses and colleagues who send out emails late at night, expecting an immediate answer—or latest by the next morning? And what to do about the need to prove that you’re on top of things by meeting that expectation? I call it the “cult of busyness”, and point to “wearing busyness as a badge of honour”. What are we to do about that, comes the question.

What I notice is that everybody is looking for an individual answer, a personal solution, as though it’s their problem to resolve. I always ask myself; can nobody see the naked emperor? It’s all very well doing all you can to manage yourself, but what if the system doesn’t leave you alone? I try to steer people towards the idea that it’s a systemic problem and needs a systemic solution, but mostly I get met with blank stares. (I hope by writing it down here and showing some graphs, it will land with more impact.)

The short answer I would offer is that the epidemic of busyness and the dearth of work-life balance is driven systemically by what I call the “primacy of shareholder value”. In other words, placing profit over people. Despite all the talk of the “triple bottom line” (profit, people, planet), it seldom happens in practice. The systemic solution is to make people matter at least as much as profit. To achieve that, we need our leaders, those high priests of profit, to do more than just pay lip service to the “triple bottom line”. To get there, we ourselves need to stop worshipping at the altar of efficiency for the sake of shareholders. We need to start walking and working among the time poor (as much as I dislike that term, I shall use it here for its poetic ease).

This is an interesting and sharp essay (and I’m not saying that because at one point Bierbaum quotes me). One of the axioms of the neoliberalism that took hold of Western governing elites in the 1970s was that corporations needed to reduce operating costs sharply, which meant in practice reducing labour costs, which in turn meant curbing union power. And both Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK took this to heart. One of the first things Reagan did after taking office, remember, was to sack 11,359 unionised air-traffic controllers workers overnight on August 5, 1981. And over in the UK Thatcher introduced legislation curbing trade-union power (by outlawing secondary picketing, for example) and, later, by taking on — and defeating — the National Union of Mineworkers.

And then came the tech industry, to which the very idea of unionisation was anathema, resulting in the growth of gigantic firms which were effectively neoliberal wet dreams in which the idea of a counterveiling power to managerial fiat was ridiculed as a quaint throwback to the era of Fordist mass production.

In that context, one of the most interesting findings to emerge from Acemoglu’s and Johnson’s magisterial survey of society’s thousand-year experience with technology is that the only periods in which technology-generated wealth was more equitably shared with the non-owners of capital coincided with the growth of counterveiling powers like unions together with societal mobilisation against overweening corporate power.

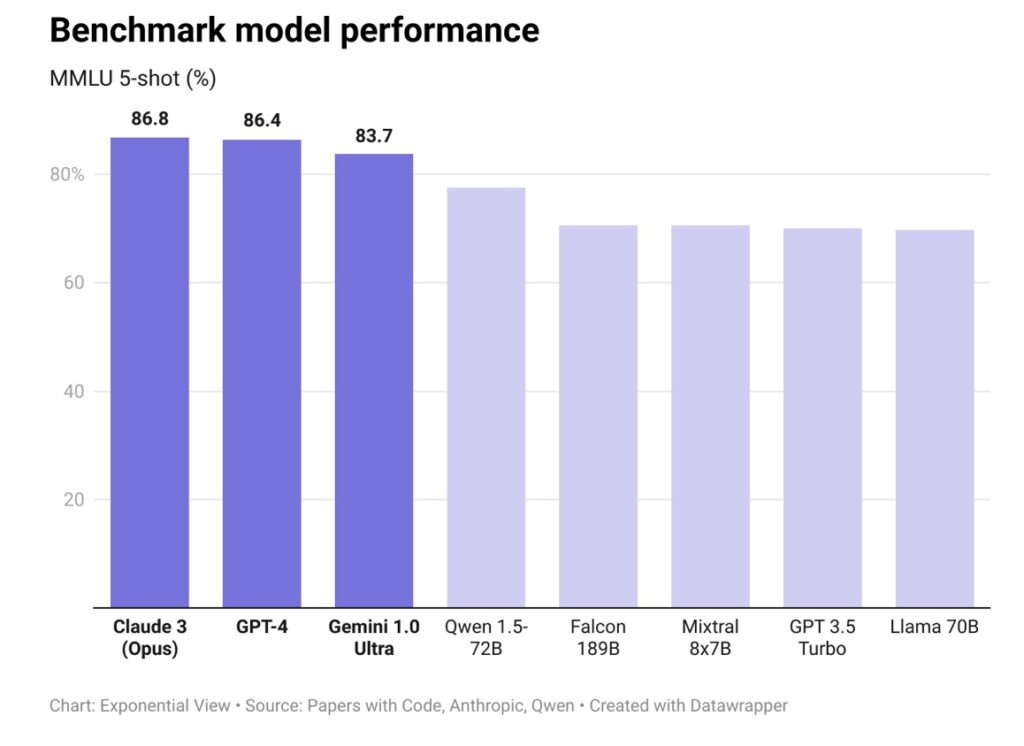

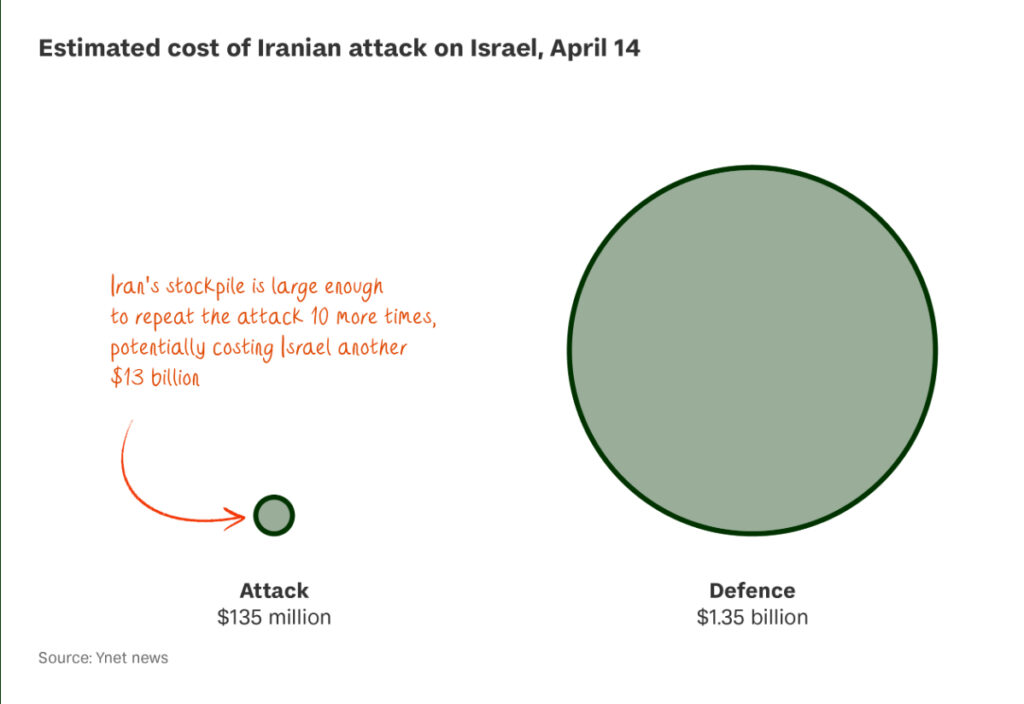

Chart of the day

Source: Tortoise Media, which commented that:

Despite the attack’s apparent failure, Tehran gathered useful information about Israel’s defences and forced Israel and the US to spend more than $1 billion in one night to counter an attack that cost around one tenth of that to launch.

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- From The Economist, 26/03/2024

“China’s government spends $6.6bn a year censoring online content, estimates the Jamestown Foundation, a think-tank in America. In one two-month period last year the authorities claim to have deleted 1.4m social-media posts and 67,000 accounts (ironically, they branded many of the posts “misinformation”). More recently officials launched an investigation into short-video platforms that were spreading “pessimism” among young people, many of whom are struggling to find jobs.”

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!